'Your planetary assembly’, 2025, is an invitation to co-create space, to experience your surroundings as part of a larger negotiation of self, community, and the world. The eight glass polyhedrons spread across Fallaize Park invite you to gather, talk, spend time, and share space with one another. Situated in a neighbourhood that includes residential, educational, and scientific facilities, the artwork welcomes visitors from early morning until late at night.

The arrangement of the forms along the park’s meandering path was inspired by models of the solar system. The colours come from the major tones of telescopic images of the planets, from Mercury to Mars to Neptune. Illuminated, these forms function as points of orientation to help guide you through the park. Knowing that Mars is behind you, for example, tells you that Earth lies ahead.

This work is open to your interpretation: you may see the polyhedra as elements, molecules, or crystals. Inspired by sites such as Thingvellir in Iceland and the agora of ancient Athens – places where people historically came together to negotiate, discuss, and debate – Your planetary assembly is a public space for everyone: visitors and workers from the nearby labs and offices, as well as members of the surrounding community. It is, I hope, a peaceful oasis that emerges from the greenery of the park, spreading out like a cluster of stars or a cloud of gas in outer space.

Sitting within this local space, you simultaneously inhabit a larger continuum, a meeting point of trajectories that reflects both community and the vastness of the cosmos. As the solar system travels through space, we too are always in motion, meeting one another at a specific time and place, each on our own trajectories. – Olafur on ‘Your planetary assembly’, 2025, created with the support of the Contemporary Art Society, which opens today in Oxford North, Oxford, UK (photo: Hufton + Crow).

Last week to see 'Olafur Eliasson: Your curious journey', at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, until 21 September 2025.

Currently part of the exhibition, 'Multiple shadow house', 2010, is a free-standing wooden framework with translucent projection screens for walls. Four of the screens are illuminated by groups of differently coloured lamps whose light blends to project vivid monochrome hues on the screens. When visitors enter the structure, they cast an array of overlapping coloured shadows on the walls. These dynamic silhouettes, visible from both sides of the screens, enlarge and multiply visitors’ every movement, inviting them to co-produce an architecture of ephemeral gestures (photo: Taipei Fine Arts Museum).

Opening June 21 at Taiwan Fine Arts Museum in Taipei Taiwan, 'Olafur Eliasson: Your curious journey' reflects on Olafur's three-decade-long career, showcasing seventeen works that span installation, painting, sculpture, and photography.

'Your curious journey' is an artistic exploration that transcends borders and engages the senses. This travelling exhibition, launched in 2024, has already received enthusiastic feedback at the Singapore Art Museum and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in New Zealand. Now, this journey reaches its third stop at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, inviting audiences to engage in an immersive dialogue exploring light, shadow, space, and perception. Afterwards, it will continue to Museum MACAN in Jakarta and MCAD Manila – Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, further deepening the connections and conversations among audiences, museums, and the world through contemporary art.

Photo: Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Long daylight pavilion is a site-specific artwork that marks the sun’s path through the sky above the city of Helsinki on the summer solstice. Curated by HAM Helsinki Art Museum, the light installation is inspired by time, the sun, and the geographical location of Helsinki. Opening 5 June, the work is Olafur's first public artwork in Finland.

“It’s a great honour for me to see my work Long daylight pavilion occupy such a key position in this forward-looking new area of Helsinki. I hope that it will rapidly become an attractive destination for residents of the neighbourhood, connecting them to the world by gesturing to the path of the sun at this location. And for those viewing it from the city as a bright light across the water, I hope that it offers a point of orientation on their horizon,” said Olafur.

Photo: HAM / Maija Toivanen

Sneak peek of Olafur's new exhibit at neugerriemschneider, opening 02 May. The lure of looking through a polarised window of opportunities, or seeing a surprise before it’s reduced, split, and then further reduced

Photo: Jens Ziehe

Auckland Art Gallery opens 'Olafur Eliasson: Your curious journey' on 7, December 2024 — a retrospective highlighting over 30 years of installations, sculptures, and photographs that explore themes of human perception, experimentation, and environmental awareness. It marks the first solo showcase of Olafur's in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Olafur describes the exhibition as a collection of diverse artworks that invite visitors to embark on their own journeys: ‘What fascinates me is how the different ways we observe natural phenomena can connect us, not just to each other, but also to the larger world around us. That’s something I try to work with in my art: experiences that welcome everyone and their varied perspectives.’

‘Under the weather’ will be on display in Auckland Art Gallery’s Te Atea | North Atrium as part of the upcoming exhibition ‘Olafur Eliasson: Your curious journey.’

Image credit: Olafur Eliasson, ‘Under the weather’, 2022; Installation view: ‘Olafur Eliasson: Nel tuo tempo’, Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, 2022 (photo: Ela Bialkowska, OKNO Studio).

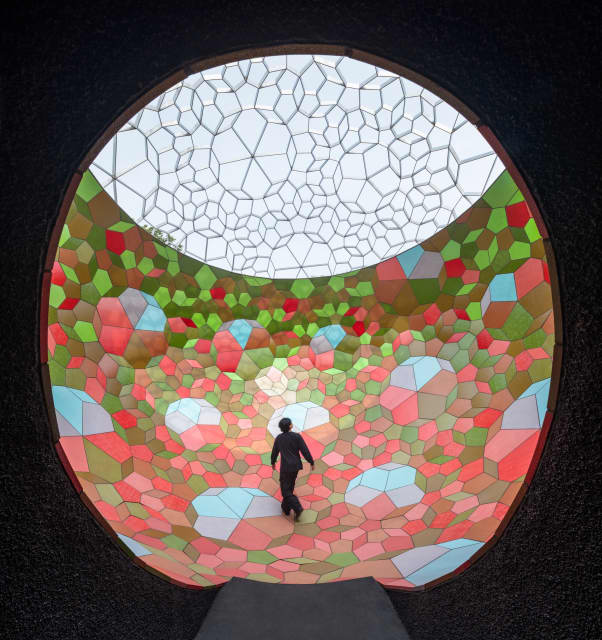

“There are no corners in Breathing earth sphere, no sense of horizon or limit. In fact, there are no walls, ceiling, or floor,” explains Eliasson. “Standing there, you may feel, simply, a sense of presence, here and now, within the sphere. Transitioning from red at the bottom to green at the top, the tiles relate intuitively to the earth, to the soil, and to the greenery of plant life. The polyhedrons conjured around you may bring associations to the crystals in the soil, the tiny nutrients that give life to us all.”

'숨결의 지구 (Breathing earth sphere)' opens today on Docho Island, Shinan County in South Korea. The installation, part of a larger initiative by Shinan County that celebrates the region's natural beauty, centers around public art projects that draw attention to reimagining the immediate environment.

'숨결의 지구 (Breathing earth sphere),' 2024; Installation view: Docho Island, Shinan County, South Jeolla, South Korea, 2024; Photo: Kyungsub Shin; Commissioned by Shinan County

Tanya Bonakdar Gallery is presenting a solo exhibition of new works by Olafur, from October 24 to December 19, 2024. 'Your psychoacoustic light ensemble' comprises two new groups of light installations and a series of recent watercolors. All of the works draw on Olafur’s continued interest in colour phenomena and the relativity of our perception, themes that for Olafur emphasise how our experiences of the world are highly individual, context-dependent, and subject to change. ‘Colour’, Olafur explains, ‘does not exist in itself but only when looked at. The unique fact that colour only materialises when light bounces off a surface onto our retinas shows us that the analysis of colours is, in fact, about the ability to analyse ourselves.'

Image: 'Your psychoacoustic light ensemble', 2024; Installation view: Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, NY, 2024. (Video: Olafur Eliasson).

“‘Lifeworld’ is an artwork I created with CIRCA for anyone who happens to move through the public spaces of Piccadilly Circus in London, Times Square in New York, Kpop Square in Seoul, or Kurfürstendamm in Berlin. The work also takes shape online in the global digital space of WeTransfer. Passing through these dynamic spaces, you might notice a blurred shape and colour crossing the advertising screens that usually display crisp, sensational imagery. At first glance, these ambiguous forms may even be confusing or destabilising. Our cities, as environments, can feel utilitarian when they are primarily dedicated to set modes of commuting or consuming.

Online spaces are also increasingly rigidly programmed to be productive and profit-seeking. I believe public spaces come to life when they host a plurality of perspectives, co-created with whoever is there at that point in time – protesters, tourists, street performers, commuters – children and adults, individuals and crowds. ‘Lifeworld’ is an invitation to contemplate who you are and where you are, here and now. The artwork relaxes your sense of depth and time in relation to everything that surrounds you, showing the immediate site anew. The rapid circulation of bodies and vehicles in real life, and information online, dissolves into the soft, slow, liminal perspectives of ‘Lifeworld’. Now these environments, like the artwork itself, are open to our interpretations.” – Olafur Eliasson on ‘Lifeworld’, 2024.

From Today, appear every evening at 20:24 local time in London, Berlin, Seoul and Online on WeTransfer (1 Oct to 31 Dec 2024), and return every evening at 23:47 EST throughout November in Time Square, New York.

Olafur Eliasson: OPEN from September 15, 2024, through July 6, 2025, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. The first major solo exhibition of Olafur Eliasson in Los Angeles, OPEN is part of the landmark Getty initiative PST ART: Art & Science Collide. Continuing Eliasson’s career-long exploration of light and colour, geometry, and environmental awareness, Olafur Eliasson: OPEN presents a series of site-specific installations responding to MOCA Geffen’s building and the atmospheric conditions of Los Angeles.

Olafur Eliasson: OPEN features over a dozen works commissioned for MOCA, along with a selection of recent works organised around the artist’s research on perception, optical devices, physics and natural phenomena, navigational instruments, and colour experimentation. Eliasson draws attention to the relativity of our perception and challenges habitual ways of seeing and experiencing the world. The exhibition is informed by the artist’s belief in the potential of inconclusiveness—the idea that every artwork contains an aspect that is radically open.

Image: 'Kaleidoscope for plural perspectives', 2024; Installation view: The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles; Photo: Olafur Eliasson

Light experiments for Olafur Eliasson’s upcoming exhibition ‘Open’ at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2024 (video: Olafur Eliasson).

Installation view of 'Olafur Eliasson: Your unexpected encounter (Senin beklenmedik karşılaşman)' at Istanbul Museum of Modern Art, Istanbul, Türkiye, until 09 February 2025. The exhibition presents an opportunity to view and explore the themes that Olafur has focused on throughout his 30-year career. His interest in subjects such as light, colour, perception, movement, geometry, and the environment meets the audience through the artworks in the exhibition (video: Canberk Ulusan).

Opening at Istanbul Modern on 07 June 2024, 'Olafur Eliasson: Your unexpected encounter' offers an opportunity to explore Olafur's three decade long practice and the themes central to it. Olafur emphasises that his works are only complete when viewers engage with them and consider this active participation to be an essential component of his work. Through the audience’s dynamic process of discovery, the phenomena Olafur presents – whether in varied contexts or scales – frequently results in unique experiences.

Image: Detail of 'Dusk to dawn, Bosporus, 2024; part of Olafur Eliasson: Your unexpected encounter (Senin beklenmedik karşılaşman) at Istanbul Modern (photo: Jens Ziehe).

Viewed from the entrance, the tunnel appears to glow in a fluctuating array of bright tones that overlap and combine to form unexpected colours. The variations in hue are caused by dichroic, colour-effect glass, a material that reflects certain wavelengths of light while allowing others to pass through it unimpeded. The glass thus appears to be a different colour depending on the angle at which the light hits the glass and the position from which it is seen. Viewed directly, the glass appears pink, with a cyan reflection on the surface; seen from an angle, a range of other colours in the spectrum between the two emerges, including oranges and yellows. As viewers move through the tunnel, the colours change constantly, drawing them onwards. The structure simultaneously seems to expand and contract accordion-like towards either end. This sense of movement is enhanced by parallel curves outlined by the angled panels.

Image: Tunnel for unfolding time, 2022; permanently installed in Fundación Hortensia Herrero, Valencia – 2023 (photo: Sharron Ping-Jen Lee / Studio Olafur Eliasson).

How can we develop more caring relationships to Earth? Today, tomorrow, and every day.

‘The ideas explored by SOE Kitchen shift constantly in scale, extending from the microcosm on the plate to our individual environments and to the planetary system with which we are all entangled. Today on Earth Day, 22 April 2024, we share on WePresent creative principles for anyone to adopt, with our belief that small impacts lead to greater outcomes.’ - Olafur Eliasson

WePresent’s Manifesto series invites activists and creatives to write 10 rules to live by. This month Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson and his studio kitchen team, known as SOE Kitchen, celebrate the connections between human beings, local produce, food and the sun as a system of energy exchange. #EarthDay

Your glacial expectations, a collaboration between landscape architect Günther Vogt and Olafur, refers in its design to the glaciers that formed the landscape around the Kvadrat headquarters, as can still be seen in the site’s topography and geology. The project does not end at the property boundaries, but incorporates the entire surrounding landscape. Building and parking lot have been integrated into the landscape.

Set directly in the rambling meadows, Olafur’s five mirrors form a series ranging from a perfect circle to ever more elongated ellipses. The mirrors reflect the ever-changing sky above and the contemplator’s own gaze, as if in the surfaces of glacial pools in Iceland. The sky opens up in the soil beneath the viewer.

This blurring of the boundaries between above and below, inside and out, finds resonance in the landscape’s melding of wilderness and garden. The dense and clearly delineated groups of trees, planted by Vogt on slight elevations, may appear to be cultivated gardens from a distance. Up close, they are in fact slices of untended wilderness. Although one might expect to be allowed to enter the wild groves, fences deny access – they are Gardens of Eden that cannot be entered.

The sheep that graze the meadows are not native to the site. Part of Olafur’s vision, they were specially brought in from Iceland for Your glacial expectations.

Image: Your glacial expectations, 2012, Kvadrat, Ebeltoft, Denmark, 2012 Photo: Annabel Elston

Reminiscent of the crystalline basalt columns commonly found in Iceland, the geometric facades of Harpa Reykjavik Concert Hall and Conference Centre were based on a modular, space-filling structure called the quasi brick. Originally developed by geometer and mathematician Einar Thorsteinn in the 1980s, following fifteen years of research into the topic, the quasi brick is a twelve-sided polyhedron consisting of rhomboidal and hexagonal faces.

In 2002, Olafur and Einar began investigating the potential for using the quasi brick in architecture. When the modules are stacked, they leave no gaps between them, so they can be used to build walls and structural elements. The combination of regularity and irregularity in the modules lends the facades a chaotic, unpredictable quality that could not be achieved through stacking cubes. As a result, the facades for Harpa are both aesthetically and functionally integral to the building.

Only the main south facades of Harpa employ the three-dimensional quasi bricks; the irregular geometric patterns of the west, north, and east facades were derived from a two-dimensional sectional cut through the three-dimensional bricks. The quasi brick modules incorporate panes of colour-effect filter glass, which appear to be different colours according to how the light hits them; the building shimmers, reacting to the weather, time of year or day, and the position and movements of viewers.

Olafur and his studio designed the facades of Harpa Reykjavik Concert Hall and Conference Centre in collaboration with Henning Larsen Architects.

Image: Façade for Harpa Reykjavik Concert Hall and Conference Centre, Reykjavik, 2013, Photo: Nic Lehoux

In 2008, Olafur harvested about fifty large tree trunks from the northern coast of Iceland. The wood, not native to that country, where less than one percent of the land is covered in forest, belonged to a mass of timber that washes up on Iceland’s shores from Siberia, carried by drifting polar ice and bleached by the sun and saltwater during its long transit.

After shipping the trunks to Berlin, Olafur then curated an urban intervention with the driftwood, inserting the massive logs into the cityscape overnight, leaving them in unexpected locations, on main plazas and small side streets alike. The trunks were placed in roundabouts, parking areas, and other in-between spaces as if they had simply drifted into the city and become entangled in its grid. This intervention, titled 'Berliner Treibholz' (Berlin driftwood; 2009), used the timber to generate small frictional dialogues, offering momentary thresholds of subtle resistance to our often pragmatic and automated relations with our surroundings.

The driftwood represents a story of migration and a narrative of natural forces. These nomads hover on the border between natural and artificial, between the normal and the unexpected, just as they float on the border of the sea and the Icelandic shore.

Images: 'Berliner Treibholz', 2009. Berlin, 2010.

'Your double-lighthouse projection' deals with the concept of ‘completing’ a work in the eye of the beholder.

‘Faced with two circular rooms of different sizes, viewers are initially invited to enter the larger space incorporating hundreds of red, blue and green fluorescent tubes encased behind a seamless translucent wall. The colour of the illuminated enclosure, flooding the perceptual field, gradually changes through a random spectrum, from pink to blue to orange and so on. At each point, the retinal after-image mixes the colours perceived before the eye, until it becomes impossible to differentiate between the two. The adjacent room, lit simply with white light, provides viewers with the opportunity to refresh their visual faculties. Always in a state of flux, the work constantly communicates new experience and meaning.’ - Susan May, Tate Modern curator, ‘Meteorologica’, from 'Olafur Eliasson: The Weather Project‘, 2003.

Image: 'Your double-lighthouse projection,' 2002. Tate Modern, London, 2004 – 2002, Tate Photography (Andrew Dunkley & Marcus Leith).

Starting in 2018 Olafur began producing artworks inspired by the phenomenon of the lens flare – the rings and circles of light that appear in a lens when it is pointed towards the sun or another bright light source. Resulting from the physics of the lens, flares are generally considered errors to be avoided in photography and film. Olafur, however, transforms these undesired flares into a central element to be explored in all its aesthetic possibilities. Originating in his long interest in light and refraction, this body of works includes projections as well as dynamic glass wall compositions like this one. Colourful panes of silvered, handblown glass are arranged according to the geometrical arrangements that result from the flare. The ripples, bubbles, and small irregularities in the hand-blown panes of glass reflect the craftsmanship that has gone into the artwork’s production and lend the shapes a fluid organic quality. The vibrant composition of overlapping circles and ellipses stretches out in front of a grey background that presents a spiralling vortex flattened into two dimensions.

Image: 'The spiralling presence of the not-too-distant future', 2023 (photo: Jens Ziehe).

‘The Flesh of the Earth,’ a multidisciplinary exhibition curated by Nigerian-American writer and critic Enuma Okoro opened recently at Hauser and Wirth, New York.

The exhibition, in the words of Okoro, ‘encourages us all to consider ways of decentering ourselves from the prevalent anthropocentric narrative, to reimagine a more intimate relationship with the earth and to renew our connection with the life-force energy that surges through all of creation, both human and more-than-human. Our human bodies—one of a diversity of created bodies of the natural world—are the primary language with which we dialogue with the earth. By acknowledging that these varied bodies are always in relationship we reawaken our awareness of the quality of those relationships, considering where we may falter or harm, and also deepen our appreciation and recognition of our interdependence with the more-than-human world.’

Olafur's work ‘Now, here, nowhere’ forms part of the exhibition.

Image: 'Now, here, nowhere' 2023, Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Los Angeles

‘The playfulness that gives meaning to our activity includes uncertainty, but in this case the uncertainty is an openness to surprise. This is a particular metaphysical attitude that does not expect the world to be neatly packaged, ruly. Rules may fail to explain what we are doing. We are not self-important, we are not fixed in particular constructions of ourselves, which is part of saying that we are open to self-construction. We may not have rules, and when we do have rules, there are no rules that are to us sacred. We are not worried about competence. We are not wedded to a particular way of doing things. While playful we have not abandoned ourselves to, nor are we stuck in, any particular "world". We are there creatively. We are not passive. Playfulness is, in part, an openness to being a fool, which is a combination of not worrying about competence, not being self-important, not taking norms as sacred and finding ambiguity and double edges a source of wisdom and delight.’ - Maria Lugones, 'Playfulness, "World"-Travelling, and Loving Perception', 1987.

Images: ‘Din blinde passager’, 2010. Tate Modern, London, 2019. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.

At the Interacting Minds Centre at Aarhus University, we run a series of experiments examining the idea of trust… Our assumption was that trust is something that can easily be eroded but is difficult to build up. We, therefore, conducted an experiment where people alternated between playing with computer agents, or bots, that were either quite willing to share or really unwilling to share, and with other people who had had similar experiences. This allowed us to create particular environments of high and low trust. Our assumption was that if one starts out in a scenario of high trust, one may be able to remain in that state. However, if one were so unlucky as to begin in an experiment under conditions of low trust, it would be very difficult to build it subsequently. In fact, this was not at all what we found. People appeared to be enormously responsive to the environment they were in, here and now. When they were playing with ‘trusting bots’, they would also display a high degree of trust. And if the bots showed a low degree of trust, then the participants also displayed a low degree of trust. Furthermore, when they interacted with other people, participants were actually rather unaffected by what had gone on in the previous round. Thus, the picture that emerged was that people seem very sensitive to the specific environment and rules of interaction that were applicable at a given time. This is potentially a very positive story – if it holds – because it appears that trust may breed trust, just as distrust breeds distrust.’ - Olafur interviewing Andreas Roepstorff, a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Aarhus, Denmark, for the catalogue of the exhibition ‘In Real life’, Tate Modern, 2019.

Image: ‘In real life’, 2019. Tate Modern, London, 2019. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.

In 'Your trust', 2014, six panes of hand-blown, coloured glass have been arranged at eye-level inside an open metal box, one behind the other, to create an array of overlapping ellipses. Each pane has been tinted a single tone of green, blue, violet, red, orange, or yellow, and a different elliptical section, ranging from a thin oval to a full circle, has been cut out to create a dynamic progression of colour and geometry. The layering of the panes produces myriad tints that shift and emerge as the viewer moves about the work.

The elliptical cut-outs allow only highly restricted views of the sheets of glass within. Each pane is visible only through the filtering effect of the others, leaving the viewer uncertain about the actual colouration of the glass sheets (photo: Jens Ziehe).

‘Entering a museum is a way of stepping closer to society, to the realities that we live in. In a museum, you are able to see things in higher resolution. You become more focused, aware. Your senses become more alert; your body attuned; your mind open. What you encounter are most often artefacts or works of art. In my artistic practice I try to hand over the authority of deciding what is important in these encounters to the visitors. My artworks strive to embody transformation rather than stability and being.’ — Olafur's statement on ‘The curious desert’ at The National Museum of Qatar in 2023.

Video: ‘OLAFUR ELIASSON, الصحراء تعانق الخيال, THE CURIOUS DESERT, 2023’, Tigerlily Productions for Studio Olafur Eliasson and Qatar Museums. Directed by Lana Daher; Produced by Natasha Dack Ojumu.